どうする? 在宅勤務

How Environmental Psychology Can Help You Work Better From Home

Interview with Dr. Sally Augustin, environmental psychologist and principal at Design With Science

Where we are influences how we feel and think. Nobody feels the same in a windowless cubicle as they do when hiking through the wilderness. However, it can be spooky to hear just how much our environment affects our behavior. Can some evil scientist really control our minds by using cool lighting, hard office chairs and gentle ocean noises?

While the answer is probably no, we could still benefit from knowing more about how design choices influence our psychology. Especially now that many of us are forced by the pandemic to work from home; defenseless before the seductive charms of our televisions and refrigerators.

To gain some insight on what I could do to stay sane and productive while locked down, I donned some suitable clothing and rang up Dr. Sally Augustin, environmental psychologist and the principal at Design With Science. She was kind enough to give me valuable tips on how to take advantage of the lessons of environmental psychology to deal with stress and improve everyday life.

Where you are is always affecting your mind

Environmental psychologists look at how surface colors influence your creativity and analytical performance; how ceiling height affects social behavior; how people respond to a certain texture against their fingertips, or their feet, for example.

We then add an extra layer of analysis to those aspects of the physical form. We consider how national culture and organizational culture influence people's experiences and expectations in a given space. We consider how different personalities will or should influence design.

Dr. Sally Augustin is a practicing environmental psychologist and the principal at Design With Science. She specializes in integrating science-based insights to develop recommendations for the design of places, objects, and services that support desired cognitive, emotional, and physical experiences.

Sally Augustin is a graduate of Wellesley College (BA), Northwestern University (MBA), and Claremont Graduate University (PhD). She holds leadership positions in professional organizations such as the American Psychological Association and the Environmental Design Research Association. Her most recent book is called Designology: How to Find Your PlaceType and Align Your Life with Design .

Also, many responses are universal. They don't depend on your culture or personality, but simply about what sort of space you're considering.

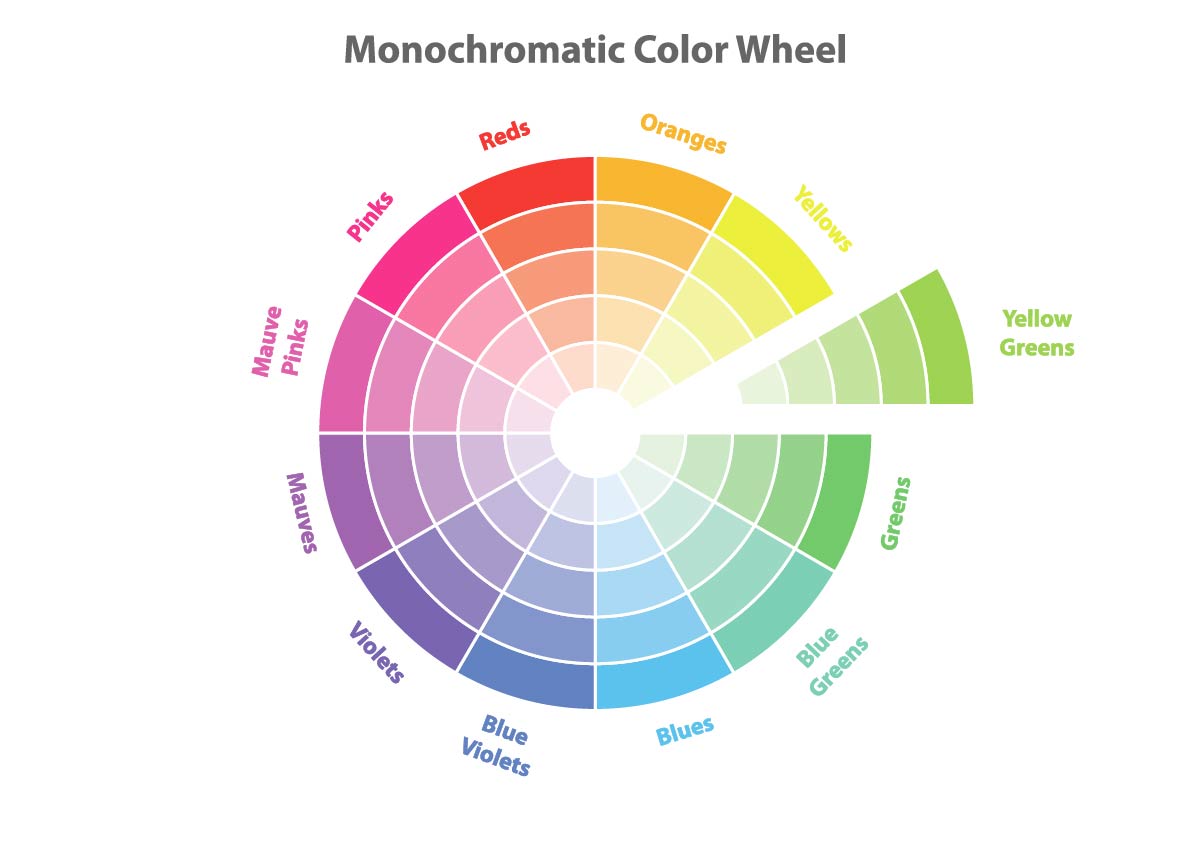

Color is a great example. Each color can be broken down into three attributes: hue, saturation and brightness. Hue is the family of wavelengths that define a color, like blue, green and red.

The color wheel sorts colors by hue and brightness.

Finally, brightness is exactly what it sounds like: how much white has been mixed into a color.

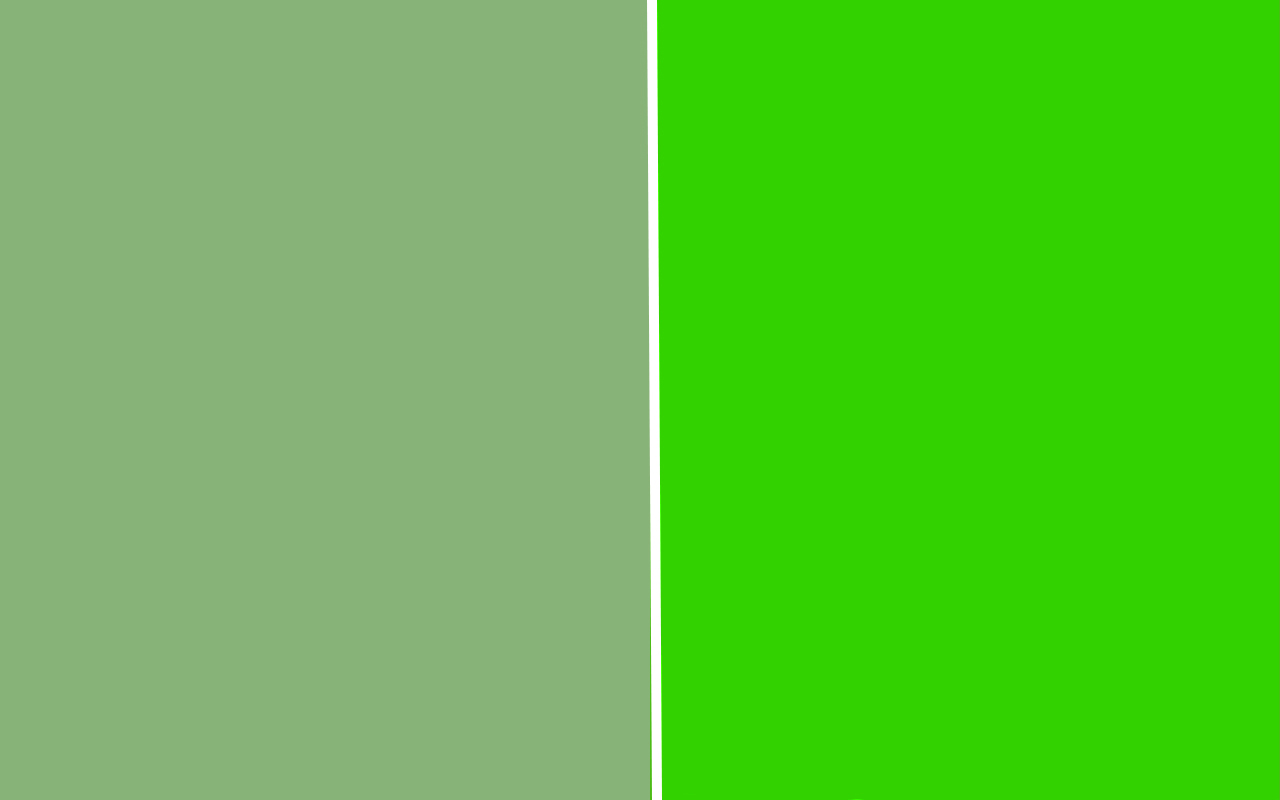

Low saturation sage green (left) versus high saturation Kelly green (right)

The opposite is also true. More saturated colors that are not too bright are more energizing to look at. Kelly green is a good example of that.

This is a constant across cultures and room types, so you should match the color to the way you use a room, whether you want a more relaxing feeling, or something more energizing.

Hall of Mirrors at the Palais de Versailles in Versailles, France

That's why in the U.S., people will buy these giant McMansions with oversized family rooms and very high ceilings, and then wonder why nobody wants to hang out in them. It's hard to just hang out, have a great time and socialize in a room with a very high ceiling.

Most people find it uncomfortable to hang out and relax in a living area with a high ceiling.

Environmental psychology seems very complex because it's new to people, but when you absorb these rules gradually, one by one, they will seem natural. In the beginning there's a lot to keep track of, but it becomes easier over time.

Each space should serve a specific purpose

With the ongoing pandemic, a lot of people are working remotely, perhaps for the first time. Even once we overcome the virus, I believe this trend is likely to continue. What do I need to consider when designing my personal home workspace?

When working from home, there's only so much you can do to really optimize your workspace. If possible, you want to be surrounded with colors that can help you relax, like the sage green with lots of white that we talked about earlier.

More importantly, if your work requires concentration, you want to minimize audio and visual distractions. You want your place to be quiet, but not completely silent—that would be freaky. This is true when working from home or at the office: You want to create a space where you can't hear other people having conversations. Our brains have evolved in a way that we can't help but pay attention to the conversations happening around us, so we have to shield ourselves from that.

I recommend playing nature sounds, but very softly. Those sounds can help keep stress levels in check. Think of the sounds you might hear in a beautiful meadow on a wonderful spring day: a burbling brook, leaves rustling, birds chirping in the distance.

The key word here is gently. You don't want torrential rainfall, no hurricane-class winds, no screaming parrots.

Also, you will reap the benefits without these sounds being loud. Think of the nature soundtrack as a subtle addition to your space; not an experience you want to share with your next-door neighbor.

When it comes to artificial light, one thing you can do—especially when working from home—is have different color bulbs for different sorts of work. Cooler light makes people more alert, which is great for analytical work. Warmer light is better for creativity and getting along with others. If you're on a call with your boss and things are a bit tense, you probably want to be in a warmly lit space.

A great example of this is Hygge; the Danish way of creating a cozy environment. Hygge uses fire light to create an environment that works well for socializing. When you think about it from an evolutionary perspective, for eons human beings socialized around fires, and our senses have likely evolved to recognize that special link.

Speaking of fire, research also shows that when we touch something warm, even after we put it down, we have warmer feelings about others. We feel more generous and empathetic. It's really interesting just how many links we've been able to find between the physical world and what goes on in our heads!

Warm light, like the light of a fire, can create an environment that works well for socializing.

We thrive in places with moderate visual complexity. By that I mean about the same number of colors, shapes and objects (in an orderly arrangement) you would find in a Frank Lloyd Wright residential interior. Looking at how those kinds of interiors are organized will give you an idea of what you're shooting for, whether at home or in an office environment.

An interior with moderate visual complexity.

The reason moderate visual complexity is ideal for us also goes back to our evolution as a species. We needed to be able to see things we found delicious, as well as things that found us delicious. In either case, we needed to see it before it saw us. Scanning our environment is more difficult when there's a lot of stuff around, which is why clutter makes us tense.

I'm particularly fascinated by how all your advice ties back to our evolution as a species! How about our relationship with nature?

We've also found that wood with visible grain can help with stress. I recommend a desktop made out of real—or at least real-looking—wood grain. The important thing is for the grain to be visible and have irregular patterns; imitation is fine as long as it doesn't have any unnatural patterns.

Looking at wood with visible grain can help reduce stress.

Gently moving water also creates a sound we find refreshing, so you could add a small fountain to your desk. That way you don't need to buy an acoustic nature track; instead you can use that tiny desk fountain everyone got as a gift from their aunt in the 90s!

A feng shui portable fountain.

Design has its limits

If I'm near the TV, I may be reminded how much I want to keep watching that show from last night. If I'm sitting close to my fridge, it becomes really tempting to just reach in and grab something. Is there a way design can shield me from these distractions?

At the end of the day, there's only so much your physical environment can do. If someone next door starts to cook a delicious meal and your window's open, you're a goner. Regardless of the color you paint your walls.

Dr. Sally Augustin's 2019 book, Designology: How to Find Your PlaceType and Align Your Life with Design

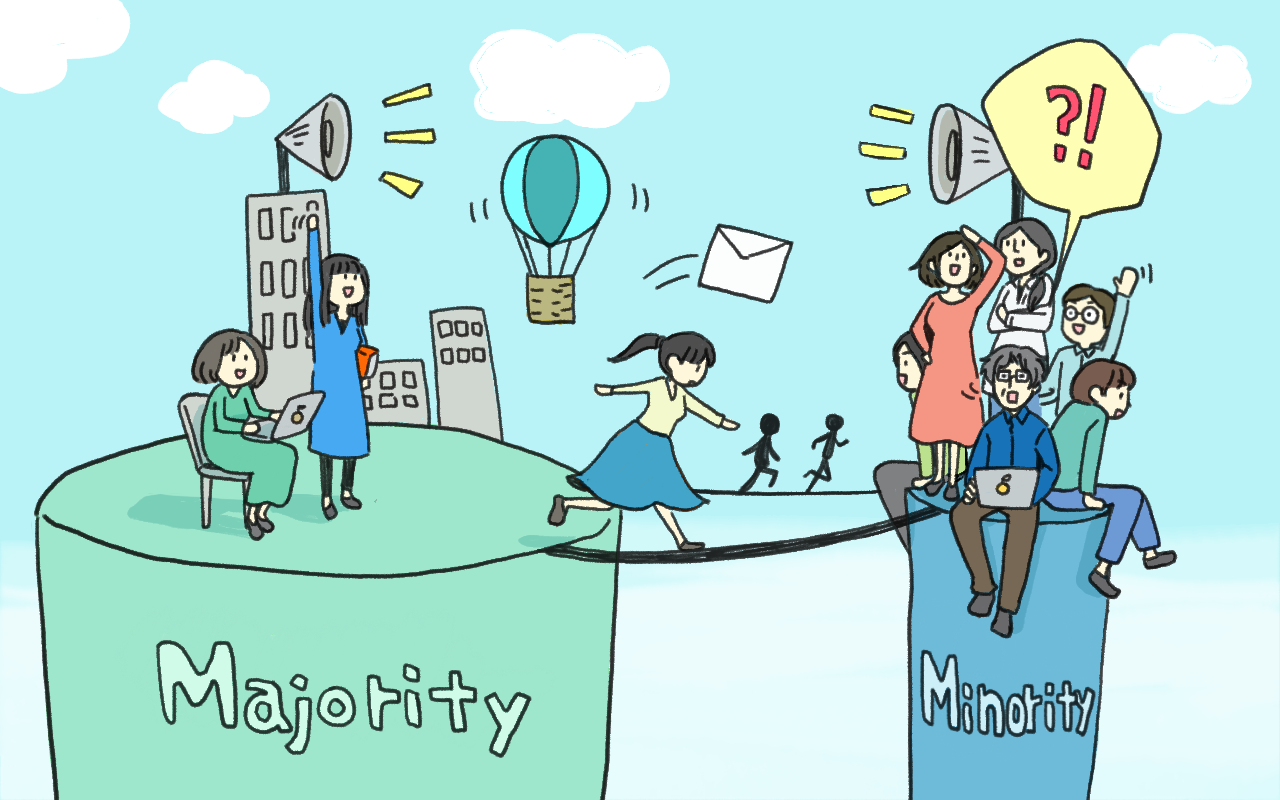

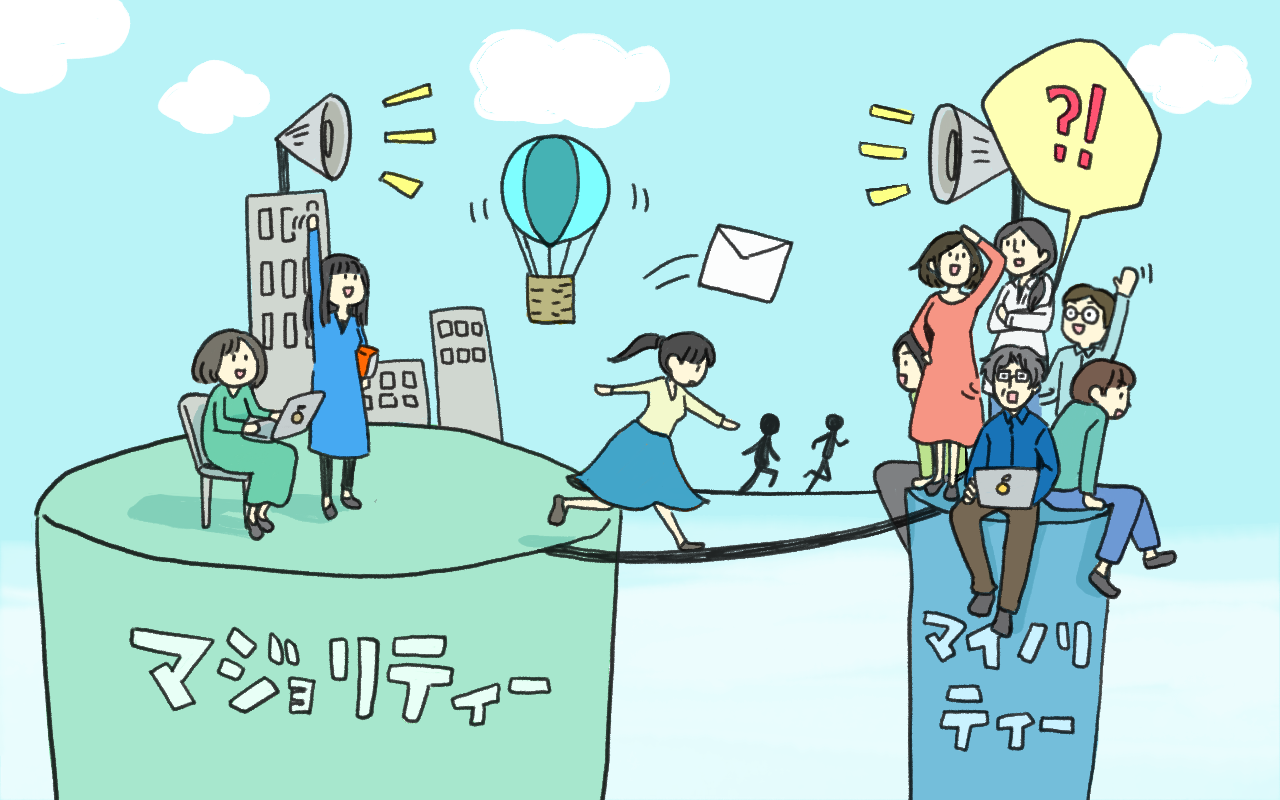

Don't go full remote just yet

We're used to thinking that humans only communicate by words and gestures, but that's not true. There are many nonverbal ways in which we signal each other. How close you stand to somebody. Whether you make eye contact when you talk. How you smell. And I'm not talking about sweat; we actually smell differently when we're happy and when we're not.

All sorts of communication channels are blocked when you're not in the same place, so if you need feedback or interaction to do something, you'll need physical proximity with colleagues. Perhaps you can prepare for those interactions by working from home, but that's not a substitute for meeting in person.

Our evolutionary history dictates that you simply can't get to know people unless you physically spend some time with them. Even as technology evolves, the complexity of physical interactions impedes what we will ever be able to do with phone or even video communication.

Don't get me wrong, it's great that we have all of these tools at our disposal—otherwise today's economy would probably collapse. But it's a stopgap. We're doing our best to make it work now because we're in a temporary crisis. I feel confident that when people are allowed to go to work again, overall, they won't try as hard with all this electronic equipment—they'll try to talk to each other face-to-face.

Article by Alex Steullet. Edited by Mina Samejima. Featured image by Dan Takahashi. Sally Augustin's photo courtesy of Sally Augustin.

SNSシェア